Railway Garden

The Railway Garden spans two full acres and tells amazing stories of American railroads in the context of a large display garden using G-gauge miniature trains.

Model Trains Done for Season

In less than a century, American railroads moved people, natural resources and commercial goods to unify and transform a frontier nation.

In less than a century, American railroads moved people, natural resources and commercial goods to unify and transform a frontier nation.

Experience captivating stories about historical events with a seamless blend of pristine gardens.

The model trains run Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from May through October, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Model Trains Done for Season

May 1- October 31, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Friday, Saturday and Sundays only

Trains run weather dependent. They are unable to run in the rain or on very windy days. Feel free to call us before arrival to confirm.

Additional fees apply for access to the Railway Garden when trains are running.

The model trains run on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays from May through October from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. If visiting the Railway Garden during this time, the admission fees are as follows:

- Non-Members: $3 per person/children 5 & under free

- Arboretum Members & PNW Students: Free

- Groups of 10+: $2 per person (must be scheduled in advance by contacting gabisarboretum@pnw.edu or 219-462-0025)

Travel Through History

“It is a grand anvil chorus across the plains and mountains in triple time: three strokes to the spike; ten spikes to the rail; 400 rails to the mile.”

– William Abraham Bell, 1866

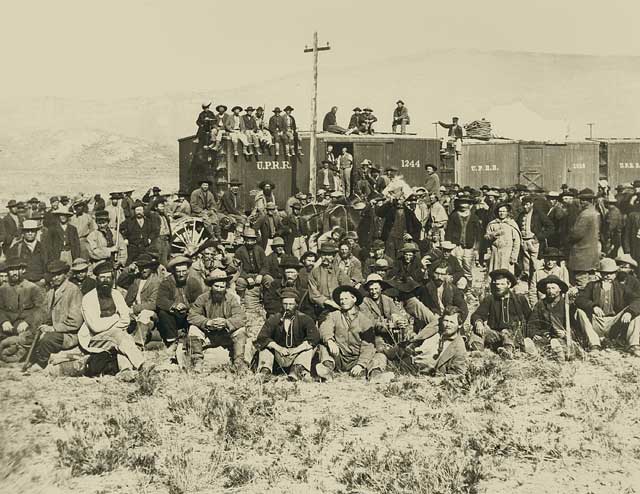

Mile upon mile, Union Pacific workers labored with military precision to move supplies, build bridges and spike rails. The crews lived in portable bunkhouses, and ate at long tables in the mess car. They spent their pay in lawless “end-of-track” towns that sprang up as the camps moved west.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, thousands of discharged soldiers – mostly Irish – joined immigrants and freed slaves to build the Union Pacific railroad. Crews laid an average of two miles of track per day, while facing hostile Indians, bad weather, and a fixed diet of beef, bread and coffee.

Image credits: Union Pacific Railroad Museum

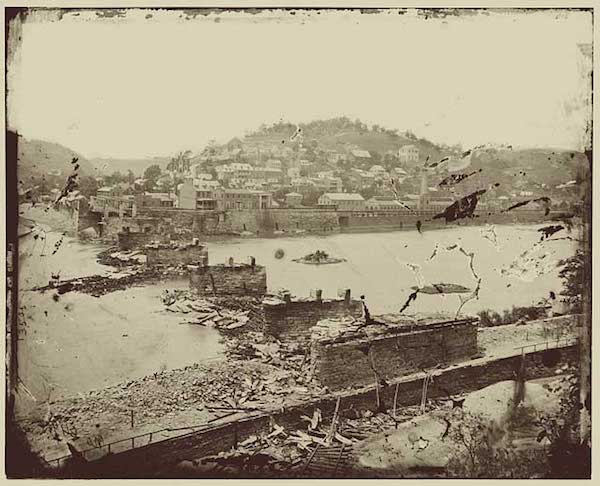

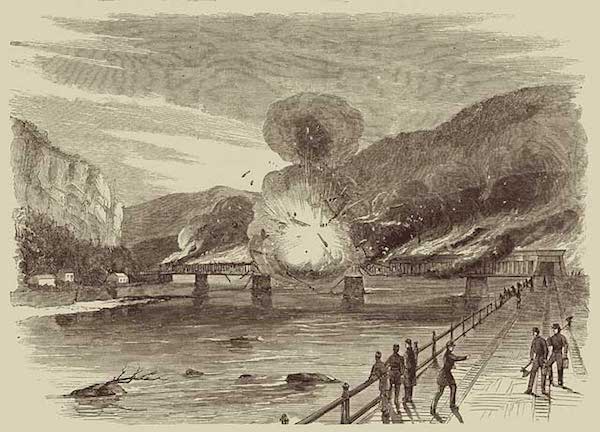

“Before leaving. . .they tore up the railroad and its station, burning the ties and heating the rails until red, then twisting them around tree trunks.”

– Lindsey Moore, Georgia, about 1864*

Both Northern and Southern forces targeted railroads. A damaged engine, track or bridge might delay an entire campaign or turn a victory into defeat.

Opposing forces just as quickly rebuilt: they restored bridges and re-set miles of tracks at amazing speed.

What do you think is happening in the diorama battle?

*Lindsey Moore was a former slave interviewed in 1937 by the Works Progress Administration

Image credits: Library of Congress

“There is nothing more important before the nation than the building of that railroad to the Pacific Coast.”

– Abraham Lincoln to Grenville M. Dodge, 1859

In 1862, as slavery threatened to split the nation north to south, President Lincoln chartered the Transcontinental – the first railroad to connect the nation east to west. As a lawyer, Lincoln had argued critical cases defining railroads’ legal rights. He later pushed his generals to use railroads during the Civil War.

Lincoln leaves Illinois for Washington, D.C.

Steamboat Effie Afton vs the Railroad Bridge

In his most famous legal case, Lincoln established the right of railroads to bridge navigable rivers. His argument: railroads were better for commerce than steamboats. Trains still ran, even when the rivers were shut down by ice and floods

Image credits: top, Library of Congress; center, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum; bottom, Putnam Museum of History and Natural Science (Davenport, Iowa)

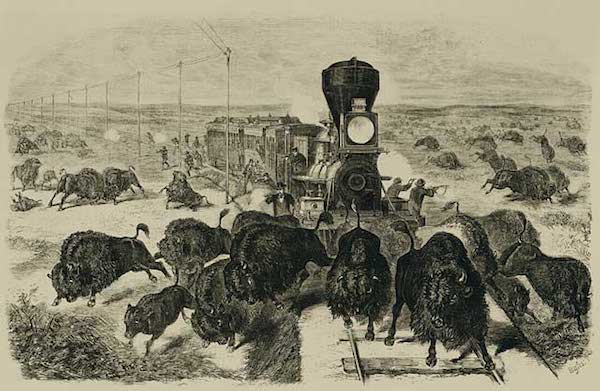

“The antelope have gone; the buffalo wallows are empty…The white man’s medicine is stronger than ours; his iron horses rush over the buffalo trail.”

– Plenty Coups, Crow Indian Chief

Thirty million bison roamed the open prairies when settlers arrived. Crow, Cheyenne, Sioux and other native people depended on them for food, homes, clothing and tools. But as railroads, farms and fences sprang up, the bison were driven out. Native people lost their food supply and were forced onto reservations.

Shooting bison from trains became an officially accepted “sport”. Bison meat, bones and hides brought in money, and officials knew that fewer bison meant fewer Indians. By 1870, the great bison herds had been cut down to fewer than 1,000 animals.

“Used to be when you left for a visit by wagon, you never knew when you’d get there. No one needed exact time. Now when those trains come through town, they’d better be exact or anything could happen, like that crash back in ‘72…”

A trip of five days by stagecoach — say, from Valparaiso to Indianapolis — took just hours by train. As people and goods moved faster and faster, citizens came to expect fresh news, merchandise and visitors every day. The economy grew to match that expectation.

Same Track, Same Time

Before 1883, people set clocks by the sun — Indiana alone had 23 local times! Trains running on unpredictable schedules could arrive at the same point at the same time and — CRASH! In 1883, to solve this problem, railroad companies created the five “standard time zones” we use today.

Image credits: Wisconsin Historical Society

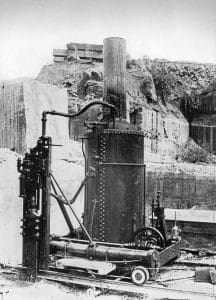

“Our town was invaded by another delegation of gentlemen last Saturday…They want 100,000 carloads of stone within the next three years.”

– Bedford Star, October 20, 1877*

At the peak of the industry, quarry-owners, mill-owners and railroad companies competed for the biggest projects, the top workers and the best railroad access.

Steam-powered channelers (see image below), move back and forth on quarry tracks, cutting deep slots to separate blocks of stone up to 10 feet tall and 40 feet long.

Workers knock wedges and shims into the slots to split off the slab. The 200-ton slab is turned on its side and cut into smaller pieces.

Derricks lift pieces as heavy as 20 tons onto waiting rail cars. As bigger and heavier blocks were cut, steel derricks replaced the earlier wooden ones.

Cut stone is carried to the mills to be smoothed, shaped and shipped. Stone sometimes goes directly to a construction site for milling.

Look in the quarry diorama for each step described.

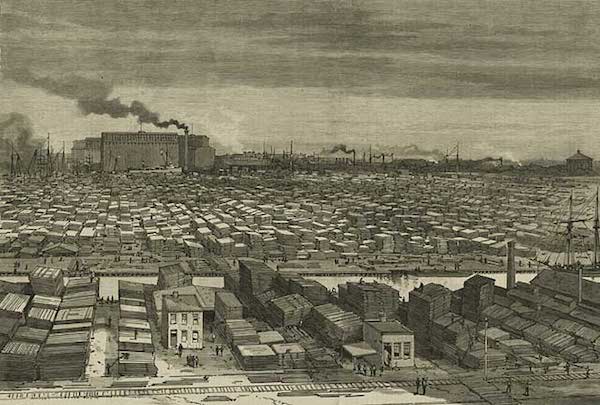

As prairies became farmland, trainloads of grain and livestock flowed eastward into Great Lakes cities. Grain was stored in massive elevators, to be bought and sold on the newly-invented grain exchange. Hogs, sheep and steers were slaughtered, butchered and packed into refrigerated rail cars bound for markets farther east.

Union Stock Yards, Chicago, about 1905

Imagine the sounds and smells of the stockyard and lumberyard.

Chicago by the numbers:

Lumber – In 1884, over half a billion feet of lumber sat drying in endless piles, ready to be shipped west.

Grain – A large grain elevator could process 24,000 bushels of corn or wheat per hour, emptying it from railroad cars at one end and loading it onto ships at the other.

Livestock – Miles of railroad track converged on the nine square blocks of Chicago’s Union Stock Yards. At peak, they processed 18 million animals a year.

Chicago’s lumber district, 1883

Image credits: Chicago History Museum

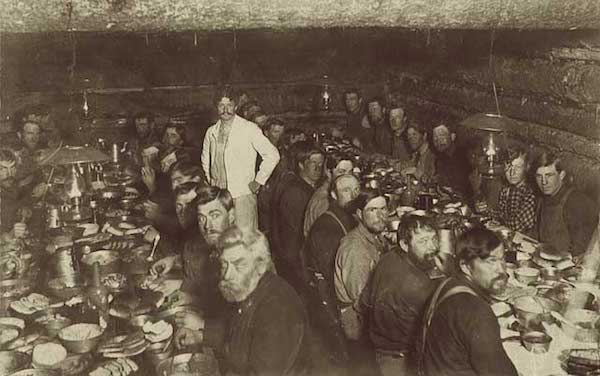

“You couldn’t talk at the table. That was one of the rules. With forty men sitting around…if they were all talking, nobody would ever get anything.”

–Ellsworth Emmett Joy

Food fueled long work days. Hearty meals of pork, beef, griddle cakes, potatoes, doughnuts, bread and pie made up for eating silently in dimly lit halls. “Lights-out” was nine o’clock, but until then lumberjacks shared songs and wild stories to scare the greenhorns. The most famous were about Paul Bunyan.

Paul Bunyan was the ultimate lumberjack. Loggers declared he could cut down acres of timber in minutes, and was so large at birth that it took five storks to deliver him. His blue ox, Babe, weighed 5,000 pounds and was seven axe-handles wide between the eyes!

Can you find Paul Bunyan and his blue ox in the diorama?

Image credits: Minnesota Historical Society

“You load sixteen tons and what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt. Saint Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go, I owe my soul to the company store.”

– Recorded by Tennessee Ernie Ford, 1955

Coal companies built “coal camps” to house miners and their families. In these isolated areas, company-owned houses were the only place to live and the company store was the only place to shop. Workers were paid in store currency called scrip (see image above); high prices kept many miners in debt.

Amidst the noise, smoke and dust, women grew vegetables or took in laundry for extra income. Black and white children had separate schools; their fathers worked together in the mines. Along with immigrant and Native American miners, they fought for better wages and safety, in labor struggles that sometimes turned violent.